|

THE

JAZZ ORGAN: A BRIEF HISTORY

Note: This is a 50+ page

document. My web authoring tool doesn't allow pagination, so you'll be

scrolling, sorry. A cassette, with keyed examples of musical pieces,

accompanied the original text, and is referenced in this document.

Copyright ©

Geoff Alexander 1988

Table of Contents:

1.

Introduction

2.

A note on organists

3.

The Jazz Organ in America

4.

Elements of Jazz Organ Technique

5.

Recording the Jazz Organ

6.

Jazz Organ: the Beginning

7.

Jazz organ: the Golden Era

8.

Afterword

9.

Genealogy of the Jazz Organ

10.

Discography

11.

Bibliography

12.

Errata and Addenda

A brief update

to the 1988 edition, written January 2004...

The paper you’ll read below

was written, well, in 1988. It was a piece I wrote to test out of a Jazz

History class so I could finally get my Bachelor’s degree. There had

never been a formal history of the jazz organ written before, and I

think it stands the test of time. I have not updated the paper, so

you’re getting my 1988 perspective, which was that jazz organ was a

dying art form. In the nearly three decades years since the paper was

written, some interesting things have occurred in the world of the jazz

organ. The paper was picked up by Keyboard Magazine, which

published an edited version in the May 1989 issue. For the article, I

lent the magazine a copy of Lou Bennett’s "Live at Club St-Germain"

record, and they reproduced the cover and transcribed a solo in the

issue, and Lou told me sometime after that the article had given him

additional recognition and had made a positive impact on his career.

This was gratifying, as Lou passed away in 1998.

Most writers will

probably cringe a bit when reading one of their older pieces, and I’m no

exception, but in spite of the winces, the paper has held up pretty

well. I was wrong about the demise of the organ, though, as the B-3 has

had a resurgence of sorts; four of the more popular newer players are

the Jimmy Smith-inspired

Joey DeFrancesco,

and

Barbara Dennerlein,

from Germany. Larry Goldings, and Rhoda Scott. DeFranceso is a very

good player in the blues-hard bop tradition, and some of his better work

has been in trio format with guitarist John McLaughlin and drummer

Dennis Chambers. Dennerlein, in the genealogy of jazz organ, would

derive from the European organists and synthesizer players as well as

having many of the elements of Larry Young. Compositionally strong,

harmonically diverse, and rhythmically adventurous, she combines strong

hand technique with stunning pedal work. Her emphasis on the tradition

of the B-3 and her willingness to expand the capability of the

instrument make her an organist worth seeing. Dennerlein has also

embraced the pipe organ, and often plays this instrument in church

concerts.

Please send me an email if

you note any factual errors in what you read below, and I’ll be happy to

correct them.

INTRODUCTION

My relationship with the

jazz organ began the day I walked into Madrid's "Whiskey Jazz" club

sometime in 1971. I had come hoping to hear Pedro Iturralde's superb

Flamenco Jazz group featuring Spain's great hard-bop tenor player, but

instead walked into a room containing a slightly beat-up Hammond B-3

organ and a small set of drums. I had never heard of American expatriate

Lou Bennett, and wasn't very thrilled at the prospect of sitting through

a couple of hours of organ, outside of a couple of Jimmy Smith numbers,

the instrument meant nothing to me, but I was stuck --- I'd already paid

the admission.

Bennett, however, put on a

startling performance of hard-driving bop standards mixed with the

occasional ballad, played so delicately that the four or five of us in

the club were almost afraid to applaud, for fear of breaking that so

intricately-weaved spell. Bennett in fact didn't so much play it as

'possess' it, grimacing, rolling his eyes skyward, and tilting his body

almost parallel to the bench to emphasize a screaming ostinato upper

octave flurry of sixteenth-notes. I was hooked.

For the next few years,

while picking up the occasional jazz organ record, I'd casually joke

that in the future, the history of music would be written in two

volumes: Pre-Electric Organ and Post-Electric Organ, as I became more

intrigued with its capabilities and less sure of myself in terms of

having an adequate historical and social context in which to place it. I

began this paper as an attempt to answer these questions to my

satisfaction, and happily ran over to the library to begin the research.

There was nothing. No

books, no magazine articles, not even a paragraph in most jazz history

books. I went home and called Downbeat Magazine. They'd never

done an article with any kind of historical perspective, just a few on

occasional individual players, but suggested I call Dan Morgenstern at

the Institute for Jazz Studies in New Jersey. Dan had nothing in his

files, and it became apparent that I'd have to start from scratch and

try to accomplish it myself.

I began to call everyone

who I felt could add something to the history of the instrument, from

critics to organists to engineers to producers. Finding no literature on

the subject, I combed used record stores in search of out-of-print organ

records with meaningful liner notes. And for better or worse, I used my

own judgment to put it all together. What I have here, then, is a

beginning, not a finished product.

It will become closer to

being comprehensive when more information is made available on recording

the instrument itself; or when an associate of Larry Young's can be

found and interviewed, so we can get an idea of where the organ was to

have progressed at the time of his premature death. It will become

historically more justifiable when musicians, critics, and aficionados

read this paper and correct (or discuss) any errors in my perspective.

This, then, is the start. It will provide the next writer

with a little more to go on than I had, and will at the same time allow

me to relate a few stories and ideas that the reader will find nowhere

else. As I say in my after word, the instrument itself is in

trouble. This is the appropriate time to begin collecting the data

pertinent to its history.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In particular, I must thank

organists Les Strand, Jimmy Smith, and Greg Hatza, producer Bob Porter,

historian Dan Morgenstern, and writer Tony Outhwaite for being gracious

with their time in allowing me to ask them what must have seemed to be

an endless barrage of questions. Jerry Welch of the General Organ

Service Company provided valuable technical information on the Hammond

B-3 organ that I could not have found elsewhere. Contributions were also

made through conversations with Leonard Feather and engineer Rudy Van

Gelder.

Special thanks to Lou

Bennett.

NOTE ON ORGANISTS

In selecting organists for

discussion in this paper, I avoided jazz musicians who play organ on the

side, but are better known for their areas of expertise (e.g. Sun Ra,

arranging and composition.) Into this category would fall people such

as Carla Bley and Clare Fischer.

There are several organists

I've regrettably never heard, such as Doug Duke, Winston Walls, Marlo

Morris, and Sir Charles Thompson, who is probably better known for his

piano work anyway. These organists are listed here because I can't

categorize them. Like any serious collector, your correspondent will

continue trying to track

these people down, and will

try to remedy this matter in the next revision. I of course welcome all

leads, names, and recorded examples.

THE JAZZ ORGAN IN AMERICA

Those wishing to find good

jazz organ records in their favorite record store may be faced with

serious disappointment. Outside of a couple of Jimmy Smith discs, and

perhaps another by Jack McDuff, the shelves in new record stores are

rarely stocked with organ records. Used record shops often prove to be a

bonanza, with many older titles drastically marked down in an effort to

move them out, and the collector can easily walk out with an armload of

worthwhile organ records for under twenty dollars. It of course

shouldn't be this way: this magnificent jazz instrument shouldn't be

relegated to the cut-out bins and the flea markets, but it is, and one

must face facts. The jazz organ is a dying instrument.

One reason for its

impending death is that the majority of record buyers in this country

are white, and the white community by-and-large has never quite been

able to embrace this instrument in a jazz or "hip" context. The

conception of the organ in the white community rarely goes beyond

organ-and-chimes at Christmas, or "ballpark organ", or

Organ-Goes-Hawaiian, or worse yet, slow, meandering organ accompanying

spoken romantic poetry. The closest most of these people get to the

organ is when they attend "appropriate" functions like weddings and

funerals, and they (and their children) are the record buyers.

In the black community,

it's a different story. Far from the funereal aura of the organ found in

most white churches, the black church has continually fostered what I

would term almost a bacchanalian approach to the instrument. In touch

the same way as the black preacher verbally walks the line between the

sacred and the profane, the organ in the black church often produces

highly-charged, emotional, fast-paced, and 'danceable’ music that bears

a direct kinship to jazz and blues. Some of the best jazz organists

began playing in church (Fats Waller and Charles Kynard, to name two),

and in this dying era of the instrument as a true force in jazz, many of

its best players will find a haven there. If, after reading this paper,

the reader wishes to hear the instrument and yet can't find a room with

an organ trio, I recommend going to a black church in Oakland, Akron,

Baltimore, or any other urban black neighborhood and attending a Sunday

evening service. The organists there are usually quite good, and

occasionally magnificent.

As an example of the

"sacred" approach to the organ found in the black community, I call

attention to the first selection on the cassette which accompanies this

paper. The organist who plays on the selection "On My Way" by Rev. C.C.

Chapman is not given credit on the record, but the listener will surely

agree that his fiery, almost frenetic style of playing is essential to

the emotional feeling displayed by the preacher and the choir on this

disc. It's particularly astonishing that this piece was recorded in

1951,during which time Wild Bill Davis was generally considered to be

the king of the jazz organ. Davis' big band-swing style of organ who

playing is foreign to this player who is closer to the style brought

forth by Jimmy Smith just a few years later.

Given this background,

therefore, it's of little surprise that jazz organ records have found

their biggest audience in the black community, a fact not lost on record

producers. Certainly albums such as Brother Jack McDuff's "Hot

Barbecue", which features a cover photo of Jack hungrily biting down on

a whole side of ribs, or Larry Young's "Heaven on Earth", which was

dedicated to Elijah Muhammad, were not marketed with the idea that

record stores in white neighborhoods would be mobbed by screaming organ

enthusiasts on the first date of issue.

Interestingly, this

black-oriented emphasis on marketing had an opposite effect in Europe,

where the organ to this day has a venerated spot in the hierarchy of

jazz instruments, a topic in itself which will be discussed briefly

later in this paper.

To conclude, the organ does

not have the crossover appeal from black to white audiences that an

instrument like, for instance, the tenor sax would have, and this fact

should be recognized as an essential element to understanding the

history of the jazz organ in the United States.

ELEMENTS OF JAZZ ORGAN TECHNIQUE

Although there are many

different kinds of organs in the world which theoretically at least are

capable of having jazz performed on them, the classic jazz organ will

have two manuals, bass pedals, volume pedal, and various stops. The best

jazz organists will usually play melody on the upper manual, comp or

sustain a drone on the lower, simultaneously be playing the bass line

with the left foot on the pedals and control organ volume the right

foot, all the while subtracting and adding stops to change registers

within the piece. A number of jazz organists interviewed for this paper

mentioned that they began to establish good fundamentals by first

learning to play piano.

While traditional organs

(e.g. pipe and theatre) have "named" stops which attempt to imitate the

sound of various acoustical instruments, such as flute and violin, the

Hammond organ does not. When Laurens Hammond introduced his Model A in

1935, he created a revolution by substituting traditional tab stops with

numerically graduated slide bars. Besides giving the player a greater

ability to add harmonics to the music, he also changed the way the

player thought about the organ. Henceforth it would be considered a solo

instrument unto itself rather than one thought of as being imitative in

the theatrical sense. The Hammond's popularity reached a crescendo with

the B3, which was in production from 1955 to 1975, and which has become

de rigueur for ninety-five per cent of all jazz organists. This

opinion among jazz organists is pervasive: when asked to sum up in one

sentence what he felt was the most important idea in modern organ

playing, Jimmy Smith immediately mentioned "the pure B3 sound." Smith,

like many others, has experimented with non-Hammond organs, only to

return, The advent of the Hammond also created a side element in the

total modern concept of jazz organ playing. Because the Hammond's AC

signal created a noticeable "pop" for each keystroke, specially designed

speakers using the roll-off technique were designed by Leslie to smooth

out the sharp attack coming from the Hammond's keyboard. Leslie speakers

revolved within the cabinet, adding a tremolo effect which, particularly

in a small room, added to the unique Hammond sound. The Hammond was the

last organ made using AC, and subsequent DC organs no longer MUST use

Leslies.

Another unique feature of

the Hammond was its method of tone production. Sound in the Hammond was

produced by means of some 91 tone wheels, each of which revolved over a

magnetic coil, and contained varying numbers of small metal "bumps"

which corresponded to the given number of cycles-per-second of the

particular note. This made the Hammond an electrical, rather than an

"electronic" organ, which produces tones by means of a sine wave formed

by an oscillator. To fully appreciate the difference in these

technologies, the reader is directed toward selection number ten on the

accompanying cassette, in which organist Les Strand plays the Baldwin

electronic organ. The baleful quality of the sine wave is apparent, even

through the frequency dividers which produce the harmonics in this

instrument.

I might add that I've

listed the technical aspects of these instruments here in the

"technique" section because a basic understanding of how these organs

operate is important in differentiating them from other keyboard

instruments: unlike the piano, the organ really can fill up a room with

sound. In fact, many piano players eventually switched to organ because,

due to the bass pedals, they would have one less musician to pay. Club

owners were equally happy, because having a B3 and a small set of drums

in a room would result in a whole evening's worth of loud, rocking

entertainment at relatively minimal cost.

Much later, of course,

rhythm boxes were added to the organ: they were tacky, uninspired, did

not lend themselves well to the creative aspects of the instrument, and

were partly responsible for the unsavory attitude of many people toward

the organ in general. The "mall organist" demonstrating auto-rhythm

organs has driven more nails into the coffin of the organ than anything

I can think of; it's a shame that so many people derive their initial

introduction to the organ in this manner, because it fails to increase

the potential audience for the few great organ players still performing.

Returning to technique,

what the listener should be listening for in order to develop a critical

ear and appreciate the instrument are: melody and harmony simultaneously

voiced, the latter either through extended chords, single-note drones,

or "comping" chords, changes in voicing, increase/decrease in volume,

and bass notes. All too often one does not hear all these elements in

one piece, but it's certainly something for which the great organists

strive. In order not to appear too dogmatic, however, exceptions to the

rule do exist: Wild Bill Davis in example six on the tape and Jimmy

Smith in example eight are interesting contrasts in that Davis makes

great use of volume control while Smith does not, whereas the opposite

is the case in terms of the rhythmic complexity of the solos themselves.

These are, nevertheless, two very good pieces by innovative organists.

One must also have an

understanding of the organist as an individual to appreciate the

difficulties in playing the jazz organ. Milt Buckner always used a bass

player because he was simply too short to reach the bass pedals. Greg

Hatza, in example number 15 on the cassette, was, at the age of nineteen

at the time of the recording, probably too young to have realistically

mastered the pedals. What he did, like many other organ players, is play

the bass by hand on the lower manual, thus giving up certain harmonic

capabilities of the instrument. Utilizing this method, the organist

would "slap" a random pedal in time with the walking left-hand bass to

provide a slight pop to the attack.

THE AURAL EXPERIENCE: RECORDING THE

ORGAN AND PLAYING IT BACK

Bob Porter, who has

probably produced as many jazz organ records as anyone, claims that one

of the main reasons for the demise of the jazz organ was the departure

of engineer Rudy Van Gelder to the CTI record label. "Nobody else could

record the damn thing," said Porter, and in truth, the number of

recordings of jazz organ made under Van Gelder is substantial. Van

Gelder was naturally reluctant to divulge any of his techniques for

recording the organ, but the set of obstacles is formidable. The Hammond

has a "booming" bass, which renders it almost inconsequential in even

Van Gelder's recordings. The volume pedal takes gain control away from

the engineer, as does the constantly changing additions and subtractions

of slide bars.

It is for these reasons

that appreciation for technique must be tempered by the realities of

the recording studio. There are times when the attentive listener will

not be able to tell whether the organist is playing the bass AT ALL,

much less trying to distinguish the various bass notes themselves. The

characteristics of the Hammond bass pedals have been a constant source

of concern to players as well as engineers. Jimmy Smith has apparently

improved the attack of the bass by removing resistors from the

circuitry, although the reality of the electrical theory behind this

concept is disputed by General Organ Service Company's Jerry Welch, who,

in his many years of repairing the B3, probably knows as much about the

circuitry design as anyone. My own suspicions are that Smith and Van

Gelder may have discovered something in this area that may warrant

further investigation once they let their secret out. In the meantime,

the most startling new development on the topic of organ bass in the

last few years has been the invention of the "Bennett Machine" by the

American expatriate Lou Bennett. In redesigning the lower manual for his

B3, Bennett also apparently altered the attack in the bass circuitry as

well. Cassette example number 17 is a ballad from his "Live at Club

Saint-Germain" album, which not only showcases this remarkable bass

design, but also features one of the best engineering jobs on the organ

to date. Unfortunately, the engineer was not given credit on the liner

notes, but the clarity of articulation in all registers nothing short of

phenomenal.

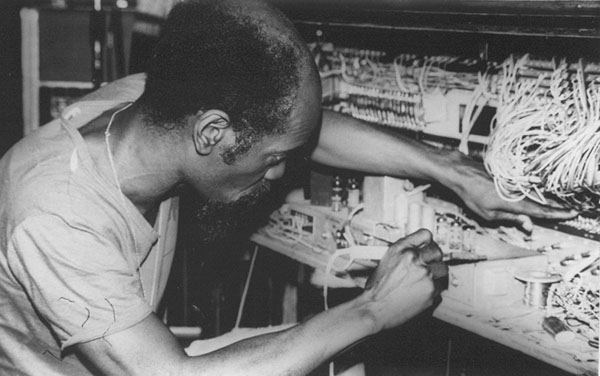

Lou Bennett building the "Bennett Machine"

- photo in the collection of Geoff Alexander

The listener would be well

advised to purchase a graphic equalizer if he or she intends to

understand and appreciate the full spectrum of sound on the jazz organ.

I wish to underscore this point as fully as possible: most speaker

systems and amplifiers will not carry the full range of harmonics

demanded by the Hammond. Jimmy Smith, in describing the beauties of the

Hammond sound, said "only two kinds of people can hear the harmonics on

the B3---me and crazy people!", at which point he mentioned playing the

organ for inmates in an insane asylum, who danced for the first time in

anyone's memory, to the sound of those harmonics. The listener can gain

similar enlightenment by using the equalizer to boost certain

frequencies, particularly in the bass range, and in the 1 kHz and 16 kHz

as well. Particularly on organ ballads, in which extensive use is made

of the extreme harmonic range of the instrument, the use of the

equalizer can be critical. Please consider it.

JAZZ ORGAN: THE BEGINNING

Although jazz organ

properly begins with Fats Waller, it is worth noting that St. Louis

pianist Fate Marable was known for playing the steam calliope on

Mississippi riverboats during the early years of the century, and

included such notables as Louis Armstrong and tenor man Gene Sedric in

his groups. Sedric forms a direct link with Waller through his work with

the famous pianist during the 1930's. Marable's music was never

recorded, and his work is not considered to be particularly influential.

Fats Waller, on the other

hand, not only initiated the organ into jazz circles, but through his

pianistic influence on people such as Art Tatum, provided the genesis

that thirty or so years later would jump over swing-style organ playing

into the bold new era fostered by organists such as Jimmy Smith and Les

Strand.

Waller, whose father was

the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, played the church

organ well before learning the piano, and it remained his favorite

instrument until the day he died. Waller's early recordings were made on

a specially-built Estey pipe organ that included a number of custom-made

theatre organ stops. These were of particular interest to him, due to

his tenure as theatre organist at the Lincoln Theatre in New York, where

for several years he accompanied silent films as well as playing solo

pieces during intermission.

In example number two on

the cassette, Waller accompanies singer Alberta Hunter on the RCA Estey

pipe organ. In utilizing his stride technique on the organ, he

emphasizes the strong one and three beats in the measure with bass

pedals, playing nothing on the pedals on beats two and four. This

augmentation of the strong beats through pedal action is not necessary

on the piano, which has a touch-sensitive keyboard. Waller therefore

provides a stride solo in a classic sense, with the right-hand melody

underscored by choppy, left-handed 4/4 patterns. Of interest is Waller's

sensitivity in accompanying Miss Hunter, providing full rhythmic and

melodic accompaniment while allowing her to articulate the song over an

understated, yet firm harmonic matrix.

Waller recorded on the

theatre and electric organ as well, making him somewhat unique in terms

of diversity. Late in the 1930's, he traveled to Europe, playing the

organ at Notre Dame at the invitation of Marcel Dupré, and stopping by

the HMV studios on Abbey Road in London to record spirituals on their

Compton Theatre organ. I will add at this point that finding recordings

of Waller's organ work is extremely difficult: I would have loved to

have heard a Waller solo piece on pipe organ, but couldn't find one, and

could only find one or two choruses of "Jitterbug Waltz", with no solo,

to illustrate his work on Hammond, The French, who always enjoyed

Waller's organ playing, actually have produced a record of Waller on

organ (RCA Black and White Series), but little is available stateside.

Waller's recording of

"Lonesome Road" (example number three) on the HMV Compton explores the

textural capabilities of the Instrument while illustrating the joining

together of the sacred and profane, spiritual and stride, that was an

essential part of the organist's personality.

In "Jitterbug Waltz",

Waller performs what may in fact have been the first recording ever of

the Hammond Electric Organ, but uses it in this case only to outline the

melody, using the bass pedal to emphasize the 3/4 rhythm by holding it

down for all three beats of the measure.

Count Basie, who learned

the organ by sitting next to Waller during informal sessions, is the

next evolution in jazz organ playing and took the organ from essentially

a stride-based instrument to one capable of performing with groups

playing swing.

Basie economized Fats'

style, as exemplified in the tune "Live and Love Tonight" (example

number five), which incidentally features Lester Young on tenor. To

illustrate the relative rarity of the jazz organ even then, drummer Jo

Jones mentioned that the organ used by Basie hadn't been played in close

to ten years and that he had to "kick it to make it go." Basie had a

sparse and "jumping" feel to his playing, and I think influenced later

organ players such as Wild Bill Davis, Milt Buckner, and Jackie Davis as

much with the sound of his band as his playing.

It was during this time

that the Hammond organ itself became an instrument of relatively popular

appeal, with organists such as Milt Herth, Ethel Smith, and Glenn

Hardman (who recorded with members of Basie's band) producing organ

records more in a popular vein. The instrument was moved further into

the mass consciousness during live radio programming, as all major radio

studios used them for background music, musical interludes, and

"punctuations" during dramas as well as commercials.

In 1949, Wild Bill Davis

appeared with a big-band influenced, rhythm-and-blues based organ style

with crescendoing, large chords and a heavy emphasis on volume pedal.

Davis, whose previous background had been as an arranger and pianist for

Louis Jordan, played the organ like a big-band, shifting constantly

through different registrations and, in contrast to Basie, playing

really large chords.

Davis' organ was the

Hammond C3, which featured a larger console than the B3. About the B3

and C3, organ historian Craig Browning writes: "The C-3 and B-3 were

produced about the same time. Both were introduced after the C-2 and

B-2 and previous to that the CV & BV. The C was a gothic cabinet and

the B was a cabinet with four spindle legs (toed into the pedal contact

assembly)."

Consensus has it that the

classic Davis recordings were made with guitarist Bill Jennings and

drummer Chris Columbus for the Okeh label in the early 1950's, now long

out of print. This may be possibly the first appearance on record of the

organ trio, one of the two standard configurations (the other being

organ-tenor) of organ-based groups during the following three decades.

In example number six on

the cassette, Bill Davis uses many of his standard techniques in this

recording made with the Duke Ellington Orchestra during the late 1960's,

especially noticeable are the "fat" chords and wide range of dynamics.

Davis' techniques directly influenced players such as Jackie Davis and

Milt Buckner; his background in R & B led to the branching off of Bill

Doggett (who, incidentally got his first gig as a referral from Davis)

from the jazz continuum to lead a host of other organ players through R

& B directly to soul and rock. He also (and boy, am I going to hear it

on this one) was probably the progenitor of the "ballpark organ" sound,

which, in its purest form, is a great example of blues-based music for

mass appeal. There is an organist in a National League city (I believe

Cincinnati) who is playing good blues-oriented jazz between innings to

thirty thousand people at a time, which coincides with the "playing for

the people" philosophy of Jimmy Smith and Jack McDuff. Eastern cities

with large urban black populations are natural venues for this type of

ongoing organ concert; in San Francisco, I have to put up with "Tie A

Yellow Ribbon" played on an organ with a tacky rhythm box played by a

tackier player...

Another influential

organist who gained popularity in jazz circles immediately before the

arrival of Jimmy Smith was Milt Buckner. Buckner's "locked hands"

technique, in which parallel chords were played with both hands "locked"

together, was originally developed by him while a pianist, and was

pervasive enough that even avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor credits

Buckner as an inspiration. As mentioned earlier, Buckner's physical

stature prevented him from playing the organ bass. He made up for this

in natural exuberance, and his later records with tenor man Illinois

Jacquet are classics in the "swing party" genre (he even plays organ

with his "big fat belly" on one of them, which, from a chromatic point

of view, renders "locked hands" obsolete.) Buckner also talked and

growled throughout his performances, which the listener will recognize

while reviewing Buckner's "Bouncing at Dawn", example number seven on

the cassette. In many ways, this is the quintessential swing organ solo,

beginning with a straight-forward swing solo in chorus one, continuing

over a high drone in chorus two, leading to added voices in the drone in

chorus three, to a locked hands section in chorus four. Incidentally,

this recording was made in 1961, and I haven't been able to identify the

first organist to use the "drone" technique, but it could have very well

been Buckner. On the other hand, since this recording was made after the

advent of Jimmy Smith, Buckner could have easily assimilated it from

Smith, who used it continually. Probably the drones most recent advocate

is Charles Earland, who, more than any other modern player, uses it as

an effective means of creating tension over a series of bars building up

to the final anticipated resolution, By the beginning of the 1950's,

then, there was a certain agreement as to the features, language,

techniques, and appropriate group setting for the organ. Influenced

mainly by Swing and R & B, it had managed to avoid the rumblings over on

5?nd Street. But the neighborhood wasn't going to stay "quiet for

long...

JAZZ ORGAN: THE GOLDEN ERA

In 1953 a young

Philadelphia pianist, frustrated because of the proliferation of

out-of-tune pianos to which he had been subjected, began to study the

rudiments of the jazz organ. After hearing Wild Bill Davis, Jimmy Smith

was initially attracted to the organ because it couldn't go out of tune,

and was determined to find a teacher of organ technique. He couldn't

find one in his area, and instead took a two year hiatus from the piano

to teach himself the Hammond, But Jimmy Smith was no ordinary young

musician: not only were both his parents pianists, but Smith himself had

studied the bass and harmony in music school, and at the age of

twenty-eight, appeared to have a clearly defined idea of what he wanted

to accomplish on the organ. First of all, his main influences weren't

other organists, they were pianist Art Tatum and bop altoist Charlie

Parker, and it would become Smith's task to bring the organ under the

influence of be-bop: before Smith's debut in 1956, it had not been done.

In fact, when Jimmy Smith

burst upon the organ scene in 1956, his impact on the instrument was so

great that he was being immediately compared with Charlie Christian in

terms of the maximum influence any musician could possibly have on his

given instrument. Through new voicings, pedal technique, and rhythmic

concepts. Smith was able to revolutionize his instrument in much the

same way that Christian changed the direction of the jazz guitar. For

one thing, Smith modernized the organ bass by becoming the first

organist to use the "walking" bass motif, which was probably as a result

of his string bass background prior to playing the organ. He instituted

bop phrasing on the instrument, and in pieces such as Dizzy Gillespie's

"The Champ" (number eight on the cassette), he punches a seemingly

relentless fury of 16th notes into his solo, using the rhythm

stops on the Hammond in a manner never used before to increase the "hard

edge" of the instrument. Smith utilizes extreme rhythmic variations in

"The Champ", even ending the piece on a more traditional coda that may

have been completely tongue-in-cheek, as is the quotation in the middle

of the tune from Grofé's "Grand Canyon Suite", which jazz aficionados

may recognize as a direct tribute to Dizzy's famous trumpet solo in the

Massey Hall version of "All The Things You Are". Special note should

also be made of Smith's comping capabilities over Thornel Schwartz'

solo, as well as his amazing one-hand chord solo during the last part of

"Champ".

Although standardizing

heavily on blues-oriented playing in the last few years, he has proved

his versatility by making albums of ballads, has done a tribute to Fats

Waller in the Waller style, and has even recorded several piano pieces.

He was also the first jazz organist to be embraced by the commercial

world, and several of his albums on Verve from the 1960's are

marginal at best. While having a real affinity for the jazz organ in

small group settings, I confess to a personal distrust of organ with big

band; the organ is almost a band in itself, and much of the time the

harmonics are buried under charts that I feel are dubious in value. One

glaring exception is the "Peter and The Wolf" recording of Jimmy Smith

on organ, with arrangements by Oliver Nelson. The writing is fresh, in

keeping with Prokofiev's ideas, and does not overpower Smith, who

instead plays several of the best (and fastest) solos ever recorded.

"Meal Time", from this album, is a typical hard-driving solo from Smith,

during which in several places he plays a repeating phrase motif that

has been used by virtually all jazz organists since. This repeating

phrase builds in intensity during a chorus and quite often is

accompanied by a drone played by the left hand prior to resolution.

The organists influenced by

Smith are legion, and along with Smith constitute a group that truly

created a "golden age" of jazz organ. A partial list would include:

Lou Bennett

Charles Earland

Greg Hatza

Richard "Groove" Holmes

Charles Kynard

Jack McDuff

Jimmy McGriff

Don Patterson

John Patton

Sonny Phillips

Freddie Roach

Shirley Scott

Johnny "Hammond" Smith

Lonnie Smith

Carl Wilson

Reuben Wilson

Before discussing these

organists, it is worthwhile to note that Smith himself, while indicating

that he has not been directly influenced by any other organ players,

does admit to enjoy listening to only one other, an obscure organist

named Les Strand, who he refers to as the "Art Tatum of the organ."

Strand,

whose father spent most of his career as a musician playing in shows on

the theatre circuit in Chicago, taught himself to play the Hammond at

the age of fourteen. He began playing in a funeral home before hitting

the lounge circuit, and was probably the purest bebop organist who ever

played the instrument. His obscurity results from a combination of

factors: an inappropriate record label (Fantasy, which had

nothing in their catalogue remotely like Strand's jazz organ, and which

refused to give much promotion to him), a non-traditional organ (he

recorded mostly on the Baldwin, which is not a "bluesy" instrument), and

technique, which was so complex that the basic jazz-blues oriented organ

trio setting would simply not have worked well with his Tatum-Tristano

influenced style. Strand rarely traveled out of the Chicago area, and

never appeared in a large East Coast city. He is rare among jazz

organists in that his first instrument was the organ itself (he started

with the Hammond at age 14), and his total recorded output consists of

three albums on Fantasy, two of which feature the Baldwin organ, and a

promotional album for Yamaha. Interestingly, neither Leonard Feather,

who produced his Yamaha record, nor Chicago jazz radio programmer Dick

Buckley, who wrote the liner notes for one of his records, knew Strand's

whereabouts, and small wonder: he retired from active playing at the

young age of 40 to pursue a teaching career in 1964, has since retired

from teaching, and now lives in Kansas City. Strand,

whose father spent most of his career as a musician playing in shows on

the theatre circuit in Chicago, taught himself to play the Hammond at

the age of fourteen. He began playing in a funeral home before hitting

the lounge circuit, and was probably the purest bebop organist who ever

played the instrument. His obscurity results from a combination of

factors: an inappropriate record label (Fantasy, which had

nothing in their catalogue remotely like Strand's jazz organ, and which

refused to give much promotion to him), a non-traditional organ (he

recorded mostly on the Baldwin, which is not a "bluesy" instrument), and

technique, which was so complex that the basic jazz-blues oriented organ

trio setting would simply not have worked well with his Tatum-Tristano

influenced style. Strand rarely traveled out of the Chicago area, and

never appeared in a large East Coast city. He is rare among jazz

organists in that his first instrument was the organ itself (he started

with the Hammond at age 14), and his total recorded output consists of

three albums on Fantasy, two of which feature the Baldwin organ, and a

promotional album for Yamaha. Interestingly, neither Leonard Feather,

who produced his Yamaha record, nor Chicago jazz radio programmer Dick

Buckley, who wrote the liner notes for one of his records, knew Strand's

whereabouts, and small wonder: he retired from active playing at the

young age of 40 to pursue a teaching career in 1964, has since retired

from teaching, and now lives in Kansas City.

Strand's version of "If I

Had You" (example number 10 on the cassette) is a tour-de-force of

dynamics, comping, and just plain magnificent keyboard technique. The

"cool" sound of the trio is a result of the fact that the guitarist 'and

the drummer were currently then working with accordionist Art Van

Damme's group, and were accustomed to playing in a relatively quiet

setting (the drummer, in fact, uses brushes throughout the album.)

Although he preferred the Hammond, Strand's father worked in the Chicago

Baldwin store and was able to introduce him to the wider dynamic range

of that organ. The Baldwin, however, did not record as well as was

expected, and therefore he returned to the Hammond for his final

recording on Fantasy, "Les Strand Plays Ellington".) The Baldwin

does emphasize Strand's horn-like quality, and in using the "vibes"

setting, actually evokes the sound of a guitar more than anything else.

Two other organists who

fall loosely into the non-Jimmy Smith category are Les Doyle and Marlo

Morris. The former played a bop-style organ in the Chicago area prior to

Strand, but apparently never recorded. Morris, who I understand was

influenced heavily by Tatum, did make a record for Columbia in

1963 called "Play That Thing", which, according to jazz writer Tony

Outhwaite, is apparently quite good. The influence of these organists on

other jazz organ players was quite limited, and I have yet to find

another player who bears any degree of stylistic similarity to Strand.

The Parker to Strand link through bebop can be compared with the later

influence of John Coltrane through free playing to organist Larry Young:

they stand almost alone as great innovators on their instruments, and

have few imitators.

While Strand was gigging in

Chicago, playing before increasingly fewer people appreciating bop

organ. Jimmy Smith was cutting a wide swath through major cities with

his more blues oriented bop, and later hard bop playing. He was also

making great early influential recording on the Blue Note label,

and soon the aforementioned generation of players was busily trying to

discover for themselves what ingredients Smith had put into the B3 in

order to achieve that kind of "cooking."

Richard "Groove" Holmes,

who achieved commercial success with his version of "Misty" a few years

back, and who replaced Smith in the Don Gardner trio even before that,

realized the danger of becoming a pure imitator of Smith, and freely

experimented with different textures, effects (wah-wah), and organs

(Hammond X-66 etc.). Many of these sounded like little more than

gimmicks, and some of the organs sounded just plain awful ("Dueling

Organs", with Jimmy McGriff, for example: a great idea, but the

instruments are almost unlistenable due to their lack of tonal depth and

range.) Holmes and McGriff, although probably great in person, are often

overly commercial on record, with weak material and generally uninspired

technique. Holmes did however buy a second-hand Cadillac hearse, in

which he hauled his Hammond cross-country, gig-to-gig while moving west

from New Jersey a few years ago, which put him in the top category of

organ lore.

Another interesting enigma

is Johnny "Hammond" Smith, who now refers to himself as simply Johnny

Hammond, and whose funk records now grace the cut-out bins of too many

record shops. It's hard to believe that this is the same organist who

displayed a great feeling for hard-bop organ soloing during his tenure

at the Riverside label, and from the recent discs one also will find

nothing to indicate that he was one of the great composers in the genre

either. The Johnny "Hammond" Smith story is not untrue: as the B3 became

harder for record companies to "sell", more and more organists traded

their instruments for clavinets and synthesizers, and their hard-bop and

blues licks for funk and soul. This is why it is essential for the

serious collector of jazz organ records to go back in time, be wary of

any disc recorded after 1975, and to try not to be too judgmental of an

organist based on hearing only one recording. I have for this reason

included a small discography in this paper, which, although not

comprehensive, will at least give interested listeners a place to start.

A number of organists

display virtuosity in one aspect of playing, but leave something to be

desired in other areas. Lonnie Smith (not to be confused with pianist

Lonnie Listen Smith), has never performed a solo on record that I have

liked, but gosh can that guy comp! He has an ear for accompaniment that

in my opinion overshadows that of almost anyone else (listen to his

early recordings with guitarist George Benson on Columbia) in terms of

rhythmic subtlety, and I have heard that he is a decent soloist in a

club setting, but his soloing just doesn't seem to transfer to disc.

Charles Kynard, on the

other hand, who died on the stand just a short time ago, left a legacy

of very good recordings, most of which were produced by Bob Porter at

Prestige. He had a "fatter" sound than most of the other post-Smith

organists, and had a remarkable sense of dynamics in terms of building a

solo to an emotional crescendo, a trait which he may have honed to a

fine point during his years as a church organist in Los Angeles. In

"Song of Delilah" (example number eleven on the cassette), Kynard

clearly displays Smith's influence on the first chorus, and thereafter

makes his own statements with varying degrees of subtlety on the slide

bars, including a nice left-handed chord drone on the 'B' section. Many

of the compositions on his recordings were written by Richard Fritz, who

also had a great talent for arrangement in an organ-led group, Kynard

was also successful at making "pop" tunes work in a jazz setting: a

Beatles song is usually the kiss-of-death on any jazz record, and yet

Charles Kynard was able to record one of the great solos in jazz organ

history over a tune as insipid as the Beatles' "Something", building one

layer of tension upon another, and using the orchestral aspects of the

organ in a thundering, yet magnificently musical manner.

Brother Jack McDuff, like

Jimmy McGriff, has made his share of uninspired, commercially-oriented

albums, so I was constantly amazed at the high regard in which he is

held by musicians and critics alike. After buying a number of

unimpressive records (all at a low cost, I can assure you), I finally

ran across the gem: "The Honeydripper" with Jimmy Forrest on tenor and a

very young Grant Green on guitar. This record is a beautiful example of

what great organ-tenor groups should sound like, from the raucous,

biting tenor of Forrest to the powerfully stated tonal textures and

dynamics of McDuff. McDuff is one of the few B3 players left gigging on

a regular basis and, despite his high regard for Coltrane-inspired

organist Larry Young, prefers to play blues. "You wouldn't listen to

our group with a score card and pencil," he says, "we play that

good-time thing."

By contrast, organist Don

Patterson, like McDuff an alumnus of the Smith school, developed a

forceful hard-bop personality on the organ. While playing within the

organ/tenor matrix, Patterson’s interactions with tenors such as Sonny

Stitt and Booker Ervin often verged on the manic. Patterson's "Sister

Ruth," (number twelve on the cassette), has the organist driving Ervin's

opening solo with a fast walking bass played on the pedals while comping

with powerful chord bursts more in the style of a drummer dropping

"bombs" than an organist. Patterson's own solo is a tour-de-force of

hard-bop organ, featuring tremendous flurries of notes in exact

phrasings, finally ending in a repeat-run over a drone followed by a

beautiful crescendo-decrescendo-crescendo on the volume pedal that marks

this as one of the great solos in modern organ. The right-hand solo over

the left-hand drone, backed by the pedal bass and right-foot volume

pedal, are among the characteristics of the B3 that make it the most

versatile and certainly one of the most difficult instruments to play in

the jazz idiom, and Patterson was a master. I use the past tense because

due to personal problems, he hasn't been heard from in many years, but

one can always hope for a resurrection. His album "Hip Cake Walk",

produced by Ozzie Cadena on Prestige, which and contains both

"Slater Ruth" as well as a phenomenal trio version of Earl Hines'

"Rosetta", is a landmark of organ recording that sounds as new and fresh

today as it did when pressed (1964).

Another post-Smith organist

who has transcended the realm of pure blues playing is Charles Earland,

who is probably also the greatest arranger for small jazz group in the

organ genre. Earland's background is as a tenor player, and he tends to

carefully arrange creative parts for the horns, which usually consist of

trumpet and tenor, occasionally augmented by trombone. In his "Is It

Necessary?" (piece number thirteen on the cassette), Earland uses the

horns to build tension into the final chorus or so, the organ soloing

over a repeated horn riff. A particular characteristic of his organ

style is the use of constantly building tension, usually created by what

he refers to as "walking around the drone," which is created by the left

hand setting up a note or chord that drones while the left foot walks

the bass and the right hand either solos or runs a repeated riff. This

technique, which was begun by Jimmy Smith but developed to its present

stage by Earland, is gradually brought to a boiling point by the

increasing pressure on the volume pedal, or, as in the case of

"Necessary", by other techniques such as adding a second chord drone

with the right hand. This heavily "emotional" style of Earland's was

realized to its greatest extent in his live recording of "Joe Brown"

(cassette example number 14.) The chart itself consists of a repeated

pattern climbing throughout the 'B' section, while the 'A' section

serves as both a base and plateau, and has no real melodic structure.

These "riffs" are mirrored

in Earland's solo, which uses all the above techniques in a highly

concise and emotional fashion, reminding me somewhat of the Illinois

Jacquet JATP days in "terms of the effect on an audience. Earland's

playing was some of the best and most consistent of the post-Smith

crowd, and his arrangements were refreshing. In recent years, however,

his records were a sorry amalgam of strings, background vocals, funk,

and whatever else the record company had lying around the studio and

under contract at the time. I know Earland didn't like this; he had

recorded a good soundtrack ("The Dynamite Brothers"), made good,

artistically successful organ records, and still couldn't make what

passes for a decent living these days. The frustration drove him into

the commercial world, but as Larry Young was to find as well, a great

jazz musician may not necessarily have the tools to make a truly good,

creative "pop" record, nor, even worse, may his producer have the

"vision" to understand how his musical star is supposed to fit in.

Earland was one of the bright lights of the jazz organ world; it's a

shame he no longer records nor, to my knowledge, plays.

Without a doubt, one of the

strangest stories in jazz organ lore is that of Greg Hatza. Possessor of

a fiery technique as well as a seemingly innate concept of jazz

phrasing, Hatza was auditioned by Sonny Stitt to fill the place of the

ailing Don Patterson after having played the jazz organ for only 1˝

years. Stitt would have hired Hatza on the spot but for altruistic

reasons not usually associated with musicians in the jazz field: Stitt

wanted the new organist to finish college first. Hatza was nineteen

years old.

There is a certain degree

of poignancy to this story because Greg Hatza showed real signs of

genius on an instrument that was, by the time he arrived, already on the

way out. One can draw parallels here between people like Buddy De Franco

on clarinet and perhaps Art Van Damme on accordion, musicians who were

quite probably the greatest jazz practitioners on their instruments

ever, and yet had the rug swept out from under them by a public ennui

for their instruments. This is not to put Hatza in their class, but is

merely an attempt to illustrate the world of the jazz organ just when he

was starting to blossom. He studied piano at an early age, was initially

interested by a Ray Charles organ disc, and was enthralled the first

time he heard Jimmy Smith. Hatza's "Summertime" (number 15 on the

cassette) displays quite a bit of the influence of Jimmy Smith, and is

important from a historical perspective as well in that finally the

music had begun crossing over to young, white players in the U.S.

Hatza's first manager was former Baltimore Colt football great Lennie

Moore, who found Hatza work in many of the clubs in the Baltimore area,

driving him to and from the train station on gig nights. "Baltimore was

a great organ town --- every room had a B3" reflected Hatza in

discussing his early years. By contrast, when asked what instrument he

played immediately after giving up the Hammond ten years later, Hatza

replied "the Farfisa piano. I couldn't afford a Rhodes," giving added

emphasis as to what the financial picture looked like for the organist

of the early 1970's. In his last days on the Hammond, Hatza was fronting

a Coltrane-oriented organ trio, playing a freer jazz much in the same

category as Larry Young. Besides teaching music in his native Baltimore,

Hatza today leads a fusion; group on the verge of a recording contract

with a major record company.

Of all the organists

In the post-Smith school,

Lou Bennett

has probably had the greatest impact on the instrument, both in terms of

influence on other players as well as technical improvements to the

Hammond B3 organ itself, Bennett was an early prodigy on the piano, and

by the age of twelve was giving lessons at his church in Baltimore.

Later he learned the tuba, giving him a particular appreciation for bass

lines that he would use eventually on the organ, which he began playing

after hearing Wild Bill Davis, although stylistically his early work is

more reminiscent of Jimmy Smith. What is unique about Bennett is that

from 1960 onward he played exclusively in Europe, thus directly

influencing a generation of European organists who otherwise may never

have had an opportunity to hear an American B3 player in a live setting.

He regularly played on the Madrid-Barcelona-Paris circuit, briefly

operated his own club on the Costa Dorada, and eventually bought a small

farm outside of Paris. Smith has said that Bennett left the US to get

away from Jimmy Smith, and has joked that every time he flies over Paris

he looks down "just to let Bennett know I'm here." In truth, Bennett's

departure for Europe may have been a combination of the relative glut of

jazz B3 players in the US as well as the traditional respect that

European jazz enthusiasts have for American expatriates. To my knowledge

he has returned to the US once, in an attempt to visit his mother, and

found his neighborhood blocked off by police, at which point he returned

immediately to Europe. As an indication of Bennett's reputation

overseas, several years ago he headlined a bill which featured Catalan

pianist Tete Montoliu as the opening act! After his set, Montoliu

returned with his tape recorder to record Bennett's closing set, an

event which took place in Terrassa, just outside of Montoliu's home city

of Barcelona.

Bennett regularly toured

with guitarists such as Philippe Catherine, André Conduant, and René

Thomas, making several recordings with the brilliant and underrated

Belgian guitarist, and generally featured another expatriate, Billy

Brooks, on drums. He also recorded with guitarist Jimmy Gourley, who

accompanies Bennett on his version of "Brother Daniel" (cassette example

number 16). In this classic example of early Bennett, the organist uses

extremely tight voicings with emphasis on the percussion stops, giving a

biting edge to his solo. Of particular interest is his impeccable

phrasing, especially in the "trading fours" segment. In this I960

recording, Bennett uses a separate bass player, and has little input

from the lower keyboard, which I will soon contrast with a later

recording, but still exposes the essence of the instrument. His comping

is superb and almost a solo in itself, powerful and understated.

In 1978,'Bennett designed

and constructed an organ to his own specifications, a B3 hybrid which he

called the "Bennett Machine." The improvements were most noticeable in

two areas; the lower keyboard was now used for multiplying various

textures such as strings and vibraphones, and the bass pedals were now

capable of a fuller sound, with purer attack and decay. It is

interesting to note that after years of research and development,

Bennett's organ would be rendered realistically outmoded with the advent

of relatively low-cost keyboards using microprocessors. Bennett’s

device, therefore is unique in space and time; in the two-hand, two-foot

school of jazz organ playing, it is the most magnificent instrument ever

developed.

I have always maintained

that the organ ballad was the truest measure of the ability of the

artist on the instrument. All inadequacies surface, so many players

refuse to play them or cleverly avoid the inherent problems by adding a

bass player so that the left foot won't have to be used and chord voices

can be addressed by the left hand. And yet, because of the difficulties,

the jazz organ retains a certain superiority over the other instruments

in that one musician can carry almost an entire orchestra, without

sacrificing the immediacy that is so much a part of the music. Jimmy

Smith and Lou Bennett are the two masters of the ballad, and Bennett's

version of J.J. Johnson's "Lament" (example 17 on the cassette) is a

classic, performed before an audience at the Club Saint-Germain in Paris

in 1980. After the bass and lower keyboard introduction, Bennett adds

the upper keyboard for the melody, all the while varying the volume via

the right foot, gradually moving into a wonderful double-time solo with

the right hand in chorus two, played over a firm yet tasteful foundation

of brushes and high-hat by drummer Brooks. The third chorus may

represent the definitive jazz organ bass solo, and the listener is

advised to note the unique attack, decay, and slide properties of the

left foot bass on Bennett's Hammond. The truly astonishing

characteristic of "Lament" is that it is, after all, a duet. The only

instruments are organ and drums.

Bennett is difficult to

find these days, and usually shows up as a brief mention in a small ad

for a jazz club in Paris or Madrid. None of his recordings are available

in the US. As mentioned before, his influence will be mainly felt in the

playing of continental organists such as Eddy Louiss from France (whose

"Dynasty" recording with Stan Getz and René Thomas a few years ago was

quite good).

While Smith and Bennett

were influencing continental organists who were also digesting quite a

bit of the music of tenorman John Coltrane, a different school was

taking shape in England. Inspired by Smith and Bill Doggett, organists

such as Brian Auger, Graham Bond, Dave Greenslade and Steve Winwood were

forming their own groups, which had roughly equal amounts of jazz,

blues, and R & B in the mix, and ultimately led to a uniquely British

style of rock. Organists such as Keith Emerson, whose deeper inspiration

was probably along the lines of Austrian classical/jazz pianist

Friedrich Gülda, led these keyboardists eventually to the synthesizer.

One the continent, an

impressive array of young organists found equal inspiration in jazz

organ and their own local burgeoning avant-garde scenes to form a

distinct European concept of modern jazz organ playing. In Germany,

pianist Joachim Kuhn's experiments with the organ in the "Mad Rockers"

group (with brother Rolf on electric wah-wah clarinet!) were a direct

link to the free playing of John Coltrane, and yet showed none of the

form of U.S. organist Larry Young. The Dutch, always at the leading edge

of the avant-garde, were represented by Jasper Van't Hof and his group

"Association PC", and Fred Van Hove. England's Mike Ratledge, although

better known as a pianist while fronting the "Soft Machine",

nevertheless created some non-traditional solos on the Lowrey organ, and

would be more considered a "continental" player than one using the

then-current British approach.

The flight of the European

organist into the world of the synthesizer can perhaps be best typified

by the story of the Czech keyboardist Jan Hammer. Hammer was equally

proficient on both the piano and organ, but his organ playing by 1968

already displayed the characteristics of the stripped-down style that

would become the norm for the synthesists of the seventies: no pedal

bass, and very little left-hand embellishment, and a heavy emphasis on

complicated right hand flurries of notes, reminding one of Coltrane's

"sheets of sound" playing on the tenor. Hammer's "Goats-Song" (example

number 18 on the cassette) was recorded in 1968 on what I believe to be

the Wurlitzer organ, and contains so much of a Coltrane influence that

one wonders also whether Hammer had heard Larry Young's "Unity" album,

which had been recorded three years earlier. Hammer's lack of reliance

on what had, until then, been traditional methods of jazz organ playing,

were indicative of the impending disappearance of the jazz organ in

Europe. The difficulty of transport, initial expense of purchase, and

problems of maintenance on an aging analog instrument were all factors

in its decline.

Perhaps the final blow to

the organ as a creative force in jazz was the untimely death of Larry

Young. Young was the sole major transitional figure responsible for

shifting away from the blues-based style of Jimmy Smith and moving

toward the free approach advocated by such musicians as tenorman John

Coltrane and pianist Cecil Taylor, and he revolutionized the instrument

comprehensively, in composition, arrangement, and technique. Like

Coltrane, Young (also known by his Islamic name, Khalid Yasin) embraced

spirituality to such a degree that he would often burn incense during

his performances while an open Koran lay on top of the organ. In what

may seem wholly incongruous, Young dedicated his raucous, blues-based

organ/tenor disc "Heaven on Earth" to Elijah Muhammad and was inspired

by such unlikely spiritualists as Albert Ayler (Young's "Means

Happiness" on the Contrasts album is almost totally based on Ayler's

sound, and Young often used Ayler's altoist, Byard Lancaster, as a

sideman).

Young was pervasive: he was

an important third of Tony Williams' Lifetime, often considered to be

the first jazz fusion group, and played and recorded with Latin rocker

Carlos Santana. The fact that Young was able to record successfully in

an avant-garde setting was an inspiration to younger organists such as

Greg Hatza, and in truth, since Young's death, no organist out of the

Smith mold has made an artistically successful album to my knowledge.

He was technically superb,

playing pedal bass, and independent left and right hands, but with a

lighter touch than previous organists, often preferring to solo

pianissimo, sometimes being only slightly audible over the drummer. Many

of Young's pieces have a strong eighth-note feel, with a heavy emphasis

on the odd beats, giving his music a surging, rocking Quality that

differs tremendously from the bop-inspired sixteenth-note feel of his

predecessors.

Young also differed from

his contemporaries in that he loved to play duets with the drummer, who

was invariably his Newark pal, Eddie Gladden. On "Major Affair" (number

19 on the cassette), he weaves a matrix of tonal colors over the

incessant, hard-driving drumming of Gladden, a piece that is more

reminiscent of the duets performed by Coltrane and drummer Rawhide Ali

than anything else recorded by any other organist up until that point.

Young frequently used the

bass-pedal drone in a solitary long note in which to introduce a piece,

ignoring the traditional way of treating a bass line, as in "Trip

Merchant" (cassette example number twenty), which eventually evolves to

the eighth-note pattern discussed above, and then remains the constant

over which all solos are suspended. Young's first solo has a wandering,

almost Eastern feel, at one point punctuated by rapid-fire bursts on the

bass pedals in two-note phrases that the microphone can barely pick up.

In part two of the solo, he

briefly restates the theme before plunging into a solo based on Young's

chording technique of emulating the bass-pedal action with first left

hand, then right, in a push-pull effect that gradually builds in volume

to the final riotous exclamation, in which chords flash by in great

bursts of speed buoyed by short rhythmic passages that signal the end of

this searing, emotional solo.

Young's groundbreaking

album is considered to be "Unity", with Joe Henderson and Woody Shaw. He

recorded an unreleased 15-minute jam with Jimi Hendrix, and made a

couple of embarrassing, commercial funk albums toward the end of his

life, in an attempt to emulate the financial successes of lesser

musicians. His death in 1978, at the age of 37, robbed the world of a

great musician and even worse, drove one of the final nails into the

coffin of the jazz organ by removing the one man who had successfully

brought new jazz music into its repertoire.

The organ world has

maintained the status quo in the ten years since Young's death, with a

few of the older ones dropping by the wayside every now and then. It's

been thirteen years since the last B3 rolled off the assembly line, and

today's keyboard player programs his bass rather than plays it. The

players discussed in this paper wrote a unique and majestic chapter into

the book of jazz; it's such a shame that so few people have read it.

AFTER WORD

In proofreading this paper,

I recognize that my own opinion as to the future of the jazz organ is

quite apparent, and perhaps a little dismal. The death of Larry Young,

the advent of the synthesizer, and Bob Porter's own feeling about lack

of proper recording techniques are all good reasons for my

less-than-satisfactory outlook. Not everyone shares my belief; Jimmy

Smith is among the people who feels that the organ will return, and that

the hiatus is brief.

Well, we'll see. The bottom

line is that the listener should get out and hear as many of these

players as he or she can, and do it now, while there is still time. The

organ is unique in that one musician controls harmony, melody, rhythm

and dynamics, does it all in real time, and has the ability to add a

wide range of overtones as well as a variety of bass line effects. And

no studio can adequately reproduce what one will hear in a "live" organ

room. By seeing as many players as possible, whenever possible, the

reader can cover his bet if he disagrees with me as to the future of the

instrument.

I'll see you at the club.

GENEALOGY OF THE JAZZ ORGAN

Some explanations are in

order for the genealogy that follows. It is meant to be a useful guide

to stylistic differences, and not dogmatic, as many organists and styles

have crossed, sometimes only briefly enough to engage in an album or

two. The headings indicate the next theoretical step upward, and is

again general; in the case of the synthesizer, for instance, both Larry

Young and the "British" organists eventually used it, so it should be

considered that these categories be examined in a horizontal context as

well.

To illustrate the futility

in trying to set a definitive genealogy, consider the following: few

would disagree that there is no apparent link between the respective

organ styles of Milt Buckner and Larry Young. Yet, Larry Young

considered avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor one of his biggest

influences, and Taylor in turn cites being heavily influenced by the

locked-hands approach of Buckner.

While the end result

differs, one fact remains unchangeable; everyone listens to everyone

else.

A graphical note: names

encircled by ovals represent non-organists who influenced the linked

organists.

THE RECORDINGS

The collector will sadly

find that most great jazz organ recordings are out of print. These

pieces are no exception. Fortunately, many of these can be culled from

the stacks of used record stores at below-market prices (store owners

may even pay you for cleaning out the organ section). Those traveling to

Europe, particularly France, will be surprised at how many good organ

discs are currently available in stores: the French love the organ, so

bring along plenty of francs...

Examples on the

accompanying cassette are as follows:

Side One:

1) Rev. C.C. Chapman, unknown

organist. NEGRO RELIGIOUS MUSIC, VOL. 3 SINGING PREACHERS,

BC # 19 (edited by Chris Strachwitz)

2) Fats Waller: "Sugar".

WOMEN OF THE BLUES, RCA LPV 534

3) Fats Waller: "The

Lonesome Road". FATS WALLER IN LONDON, Capitol T10258

4) Fats Waller: "Jitterbug

Waltz". A LEGENDARY PERFORMER, RCA CPLl-2904(e)

5) Count Basie: "Live and

Love Tonight". SUPER CHIEF, Columbia G 31224

6) Duke Ellington, Wild

Bill Davis on organ: 70th BIRTHDAY CONCERT, Solid State SS 19000

"Black Swan"

7) Milt Buckner: "Bouncing

At Dawn". CHICAGO, MARCH 1961 Musidisc 30 JA 5166 (France)

8) Jimmy Smith: "The

Champ". JIMMY SMITH, Blue Note Re-issue Series BN-LA400-H7

9) Jimmy Smith: "Meal

Time". PETER AND THE WOLF, Verve V-8652.

10) Les Strand: "If I Had

You". PLAYS JAZZ CLASSICS, Fantasy 3242

11) Charles Kynard: "Song

of Delilah". PROFESSOR SOUL, Prestige 7599

Side Two:

12) Don Patterson: "Sister

Ruth". HIP CAKE WALK, Prestige 7349

13) Charles Earland: "Is It

Necessary?". INFANT EYES, Muse 5181

14) Charles Earland: "Joe

Brown". KHARMA, Prestige P-10095

15) Greg Hatza:

"Summertime". THE WIZARDRY OF... Coral CRL 757493

16) Lou Bennett: "Brother

Daniel". QUARTET, RCA Camden 900.078 (France) May have also been

released in US as "AMEN"

17) Lou Bennett: "Lament".

LIVE AT CLUB SAINT-GERMAIN, Vogue VG 405-502609 (France)

18) Jan Hammer:

"Goats-Song". MALMA MALINY, MPS 15217 (Germany)

19) Larry Young: "Major

Affair". CONTRASTS, Blue Note BST 84266

20) Larry Young; "Trip

Merchant". MOTHER SHIP, LIBERTY/UNITED/BLUE NOTE CLASSIC LT-1038

DISCOGRAPHY

Once again, this is not

comprehensive, but instead contains a number of records "tried and

true." All titles are listed alphabetically, by performer.

COUNT BASIE

- Super Chief, Columbia

G 31224

LOU BENNETT

- Jazz Session (also

called "Enfin") RCA Camden CAS 260 (Spain)

- Quartet (also called

"Amen") RCA Camden 900.078 (France)

- Meeting Mr. Thomas

(under Rene Thomas) Blue Star 80.708 (France)

- Live at Club Saint-Germain

Vogue VG 405/502609

MILT BUCKNER

- Chicago, March 1961,

Musidisc 30 JA 5166 (France)

- Jazz At Town Hall

(under Illinois Jacquet) JRC 11433

- Genius at Work! (under

Jacquet) Black Lion 30118

WILD BILL DAVIS

- Trio sides w/Jennings

& Columbus, 78 rpm on Okeh label

- 70th Birthday Concert

(under Ellington) Solid State 19000

JACKIE DAVIS

- Easy Does It, Warner

Bros. 149'7

BILL DOGGETT

CHARLES EARLAND

- Living Black!,

Prestige 10009

- Live At The

Lighthouse, Prestige 10050

- Dynamite Brothers

(Soundtrack), Prestige 1008?

- Kharma, Prestige 10095

- Infant Eyes, Muse 5181

- Pleasant Afternoon,

Muse 5201

JAN HAMMER

GREG HATZA

- Wizardry of, Coral

757493

- Organized Jazz, Coral

757495

RICHARD "GROOVE" HOLMES

- Soul Message, Prestige

7435

JOACHIM KUHN

- The Mad Rockers, Goody

30005 (France)

CHARLES KYNARD

- Professor Soul,

Prestige 7599

- Afro-Disiac, Prestige

7796

- Wa-Tu-Wa-Zui, Prestige

10008

- Charles Kynard,

Mainstream 331

EDDY LOUISS

- Dynasty (under Stan

Getz), Verve V6-880?

BROTHER JACK MC DUFF

- The Honeydripper,

Prestige 7199

- Hot Barbecue, Prestige

7472

JIMMY MC GRIFF

- Dueling Organs (with

Groove Holmes), Quintessence 25261

DON PATTERS ON

- Hip Cake Walk,

Prestige 7349

- Why Not..., Muse 5148

SONNY PHILLIPS

- Black On Black!,

Prestige 10007

JIMMY SMITH

- At The Organ, Blue

Note 1575

- Plays Fats Waller,

Applause ^318 (Blue Note re-issue)

- Plays The Standards,

Sunset 5175 (Blue Note re-issue)

- Peter and The Wolf,

Verve 8652

- Jimmy Smith, Blue Note

LA 400-H2 (Re-issue)

JOHNNY "HAMMOND" SMITH

- A Little Taste,

Riverside 9496

LES STRAND

- Les Strand, Fantasy

3-231

- Plays Jazz Classics,

Fantasy 3242

- Plays Ellington,

Fantasy

THOMAS "FATS" WALLER

- Women of the Blues

(Anthology), RCA LPV 534

- In London, Capitol T

10258

- A Legendary Performer,

RCA CPL1-2904(e)

LARRY YOUNG

- Unity, Blue Note 84221

- Contrasts, Blue Note

4266

- Heaven on Earth, Blue

Note 84304

- Mother Ship, Blue Note

Classic (Liberty/United) LT-1038

BIBLIOGRAPHY

As mentioned earlier,

source material for this topic is scarce, and at least one pertinent

article (Tony Outhwaite's "Organ Trios Still Roar", in the Winter '78

Jazz Magazine) I've yet to see.

BOOKS

Berendt, Joachim;

translated by Morgenstern, Dan. The Jazz Book. New York: Lawrence Hill &

Co., 1975

Douglas, Alan. The

Electronic Musical Instrument Manual. Fifth Ed. London: Sir Isaac

Pitftan & Sons, 1968

Feather, Leonard. The

Encyclopedia of Jazz. New York: Bonanza, 1960

Judd, F.C. Electronics in

Music. London; Neville Spearman 1972

Machlin, Paul S. Stride:

The Music of Fats Waller.

Boston: G.K. Hall & Co.,

1985

ARTICLES

Hennessey, Mike. "Organic

Groove: The Natural Soul of Richard Holmes." Downbeat, 5 Feb. 1970, 16

Morgenstern, Dan. "Mellow

McDuff." Downbeat, 1 May, 1969, 19

Peterson, Edward. "The Rich

History of the Electronic Organ." Keyboard, Nov. 1983

Siders, Harvey. "Jimmy

Smith: A New Deal for The Boss." Downbeat, 15 Oct., 1970

ADDITIONAL NOTE: Some of

the best information on jazz organists is still to be found in the liner

notes on the recordings. While granted that the job of the writer is to

sell records, it still is refreshing to note a bias in favor of the

organ for a change. Notes such as Michael Cuscuna's on Larry Young's